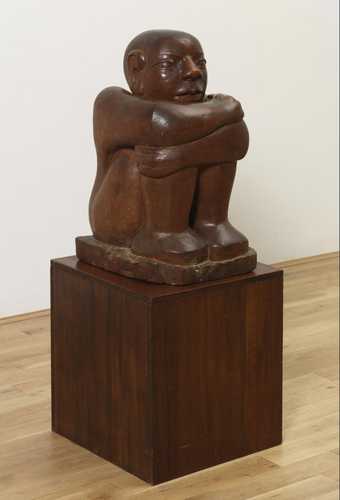

Ronald Moody

The Onlooker

(1958–62)

Tate

I don’t paint so that people will understand me, I paint to show what a particular scene looks like.

– JMW Turner

Should you (like me) wander among the many mesmerising paintings and sculptures in Tate Britain, you may come across The Onlooker 1958–62 by Ronald Moody. This sculpture speaks of the artist’s role in society. It goes further to explain Moody’s work as a reflection of his experiences in both Europe and the Caribbean, existing in a perpetual state of friction. It’s here, in this perpetual state of friction, that I find myself much of the time.

I walk in to most places feeling as though everything is not as it seems. This speaks to a lot of the work I do as a writer, and during my time at Tate Britain, walking and gisting with a helpful staff member, was no different. I’m staring at paintings such as Johan Zoffany’s Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Ayah 1786, and I’m drawn back to John James Baker’s painting The Whig Junto 1710. Unpacking these paintings – whether they portray the turbulent political climate of the time or the decisions of those in power that impacted on marginalised communities – and the task of looking beyond the beauty of these images, had us, on multiple occasions, at a silent standstill.

When I was training to be a youth worker, I came across an image titled My Wife and My Mother-in-Law, an optical illusion that can be perceived as depicting either a young girl or an old woman, depending on the person looking. At a glance, William Beechey’s Portrait of Sir Francis Ford’s Children Giving a Coin to a Beggar Boy 1793 appears to show the kind of empathy we would wish for the world. It depicts Sir Ford’s son and daughter giving money to a boy in need. The reality, it is argued, is much darker. Ford was anti abolition and claimed, in parliament, that the living conditions of British people in poverty were far worse than the enslaved people living in the Caribbean. Initially, empathy rose in me as I looked at this image. My kindness was weaponised without my knowing it. I realised that I hadn’t fully interrogated this image but had rather taken it at face value. Without that additional piece of context, I had completely missed the impact that this story had had on a whole section of society.

Turner said, ‘I paint to show what a particular scene looks like’. Now, whether you are an artist or not, as you enter each space, I feel that there are some considerations to bear in mind:

What is this space asking of me? How might these images impact someone other than me? How does my experience impact the amount of empathy I feel here?

Each room you enter adds to an ever-evolving story of history. The longer you stay transfixed on a painting or description, the more layers you peel off. New sides of yourself, whether good or bad, are uncovered. Emotions you never realised you inhabited are revealed.

When you are readying yourself for this walkthrough, consider Moody’s The Onlooker and the role you play in society. Take your time with this interrogation; don’t rush the process.

The Onlooker was purchased in 2016.

Yomi Ṣode is an award-winning Nigerian-British writer. His debut poetry collection, Manorism is published by Penguin Press.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in